Quite unlike contemporary art created to please the eye and meant to outlive the artist, we explored the Tibetan Buddhist art of Mandalas (mon-dah-lah). The concepts around this art far outweigh the material with which it is made – it’s not about the painting or the sand, it’s a lot more.

A mandala [or the process of creating one] is used by practitioners to focus their attention during meditation, and is known as a ‘yantra’ or instrument [and not an end in itself]. Meditation being one of the prime practices in Buddhism, involves focusing your undivided attention to an object, letting thoughts go as they come, and brining your attention back to the object.

If you want to know more about meditation, take a look here. The term originates from a Sanskrit word that can be loosely translated as ‘circle.’ The Tibetan word for mandala, ‘dkyil-khor’, literally means ‘that which encircles a center.’

Capturing the complex design of nature

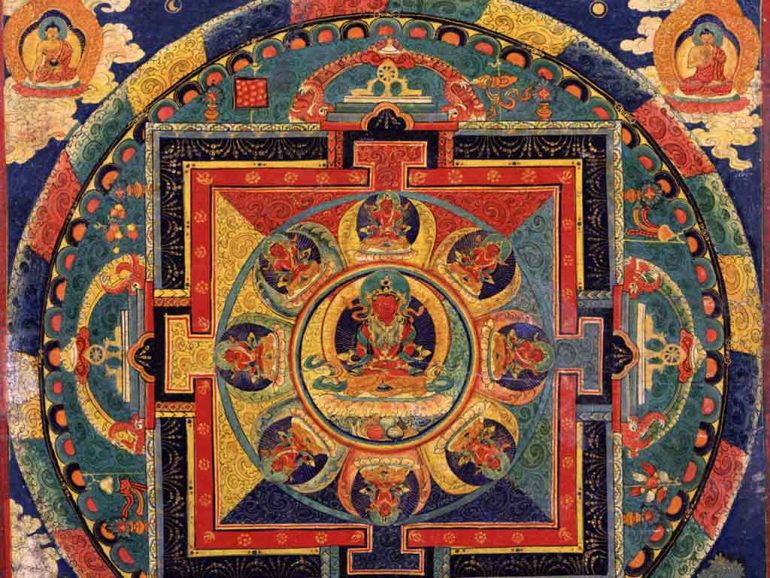

The mandala’s design, however, is much more complex than the name would infer. It is meant to represent an imaginary palace that can be focused on during meditation, and contains deities which serve as role models, with the principal deity in the center of the image. This palace is surrounded by an outer circle of flame, which is said to represent wisdom, and an inner circle of eight charnel grounds, which is said to be a reminder of the Buddhist teachings of impermanence, that is, to remember the transient nature of our lives and the constant cycle of samsara (birth, death and rebirth).

Although mandalas usually adhere to this structure, they vary in terms of design, color and other attributes, making many of them unique and beautiful works of art, with each one teaching a unique lesson. In most of their incarnations, they are meant to represent the universe as well as the nature of life.

A form of collaborative art

Mandalas are usually designed in groups, with each individual expressing themselves within the framework of the overall design, and often serving as an exercise to unify the group. One of the most common ways of designing a mandala is with sand. Buddhist scripture states that mandalas constructed from sand emit positive energies to the environment as well as the people who view them.

They’re destroyed shortly after creation [What? Why?]

Mandala sand painting is believed to have been introduced by Buddha himself, and these are believed to promote purification and healing. These intricately made mandalas are often destroyed after days or weeks of working to perfect them, to remind practitioners of the fleeting nature of visible forms and the perils of attaching oneself to them. Mandalas can also be made of cloth (that may look like a 2D architectural blueprint) or rarely, as a 3 dimensional structure.

As beautiful as these mandalas are, the meanings inherent in their design and creation elevates them far beyond ordinary artwork. Although usually used as a meditation tool intended to guide the practitioner towards becoming one with the universe, the art of this is not an easy one to achieve. However, it speaks a great deal about aesthetics and their symbolic meaning and effect on spirituality.

Mandalas represent not only a journey but can also reveal the inner emotions of an individual designing them. At the same time, they remind us of the wonders of this impermanent life – serving as Buddhism’s reminder to the world that beautiful art need not necessarily appeal solely to the eye, but to the spirit as well.

To learn how to create your own mandala, click here.

A bit of history

Mandalas came about with Tantric Buddhism in India. Buddhism, the religion of peace and enlightenment that follows the way of Gautam Buddha (born Prince Gautam Siddhartha) has a long and rich cultural history. Although Buddhism originated in India, it spread across Asia to places like Tibet, Korea, Japan, and many others besides. Like most religions, it began to develop its own style of art and architecture, which was infused with each country’s unique take on it.

Tantric Buddhism was a movement started in eastern India around the 5th or 6th century, which gradually became popular in Tibet, becoming the dominant form in the 8th century.