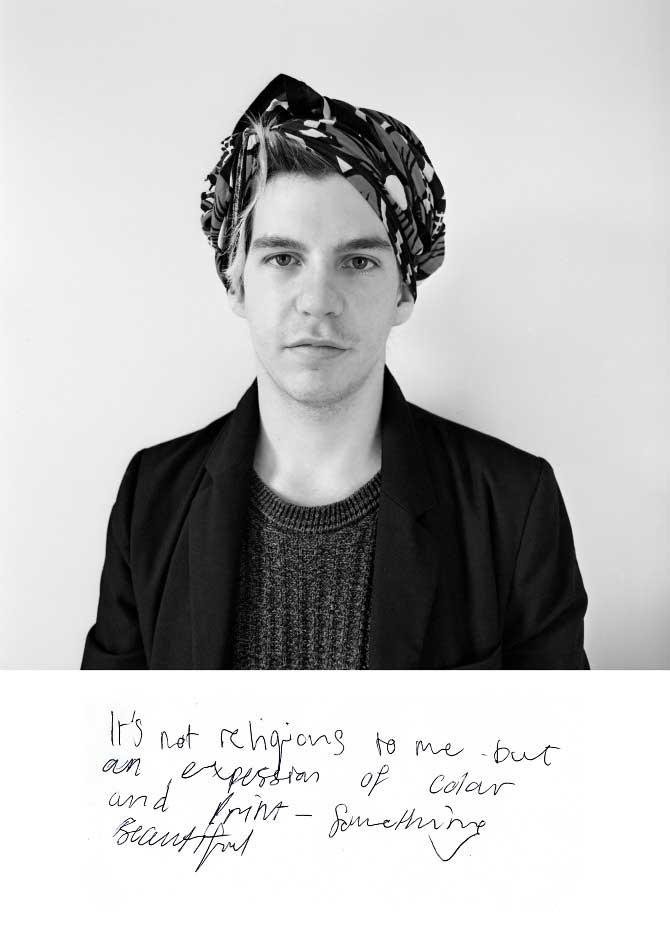

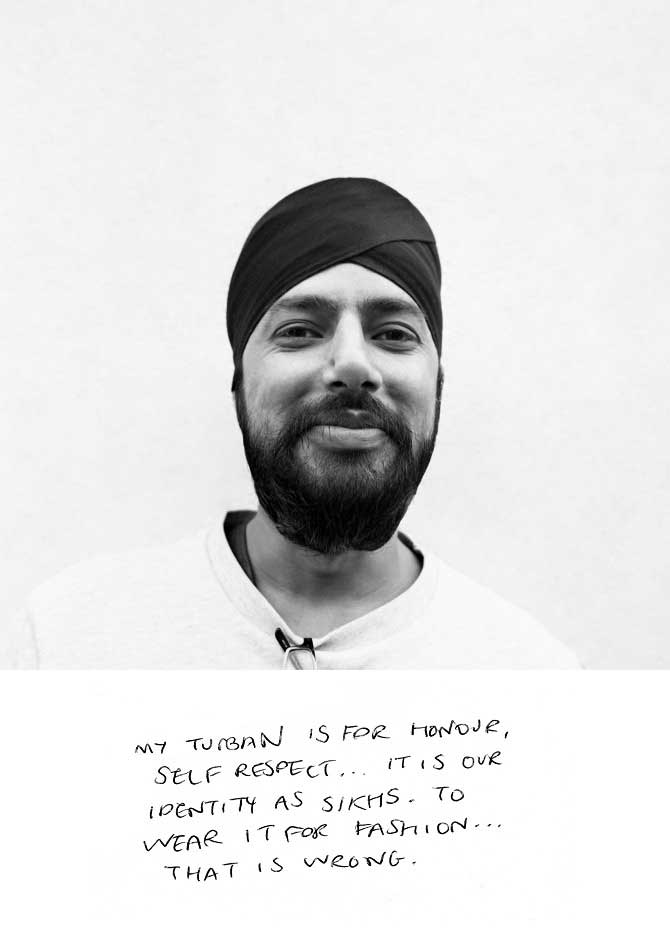

Let’s start with the basics: cultural appropriation is the adoption of aspects or symbols of an oppressed culture by its oppressor, often for mercantile intention or just to ‘look exotic’.

Appropriation is different from appreciation in that the perpetrator pays no heed to the context, history, cultural or religious significance of the symbols he/she appropriates. An appropriator cherry-picks and crops off the marketable fragments of a wounded culture, glamorising or commercialising them, without showing reverence to the culture, its people or their struggle. The original wearer of this culture, conditioned by the nuances of white socioeconomic privilege and reminders of a colonial past, feels outdone in his own skin and unwelcome in his own home. Deprived of the ownership of a culture they weaved for themselves, to the appropriated, this is a blatant reminder that imperialism is not dead.

That said, appropriation is not the same as exchange. Exchange is informed, well-intentioned and foremost, reverent of a previously oppressed society’s ownership towards its culture. It recognises that culture is often safe haven to minorities, and celebrates and explores its gamut with them.

Cultural appropriation is wrong because there is a clear and demarcated power dynamic between the powerful and powerless. There is a distinct, lop-sided distribution of control and authority that, with a refined subtlety, drives the oppressed out of their own home. It puts the oppressor in the position of consumer whence the oppressed continue to be consumed: all this is often disguised fashionably and does not receive opprobrium under the excuse of ‘good intention’ and ‘appreciation’.

When Kanye West adduces his 21 Grammy awards, not one of them received against a white artist, to prove the increasingly appropriated and racist nature of the Grammy’s in a genre that is a direct product of the black civil rights struggle, we can confirm this is a recurrent theme in the industry. Fortunately, due to the growing discourse on racial violence in general, the debate on black cultural appropriation is relatively emergent on the forefronts of pop-culture. Celebrities that continue to scythe black culture receive more opprobrium than ever before, featuring backlash of brilliant commentators like Amandla Stenberg and Azalea Banks.

As Azalea Banks conveyed eloquently:Appropriation of black culture is telling white people ‘you can do anything, you can use anything regardless of whom it belongs to and flaunt it” and is telling black people “you don’t own sh*t – not even the sh*t you made for yourself.’ The recent recognition of this problem is progress in itself. “

- Blanks (continued): When Katy Perry donned an ‘exotic’ cherry-blossom-kimono, white-face demure ensemble, wearing culture like it was a halloween costume, the backlash was deservedly rife.

However, one demographic of society remains startlingly complicit and mute on this conversation: Indians, 1.2 billions of us and most abet or excuse appropriators, with very few voices as exceptions. As an Indian, I cannot ignore the very real extrapolation of this trend in my own culture.

But the problem is much, much worse: it isn’t just that we are complicit to appropriation, we tend to support our appropriators. Most young Indians are completely desensitised towards cultural disrespect because we ourselves do not take any pride in our culture unless it is validated by white people.

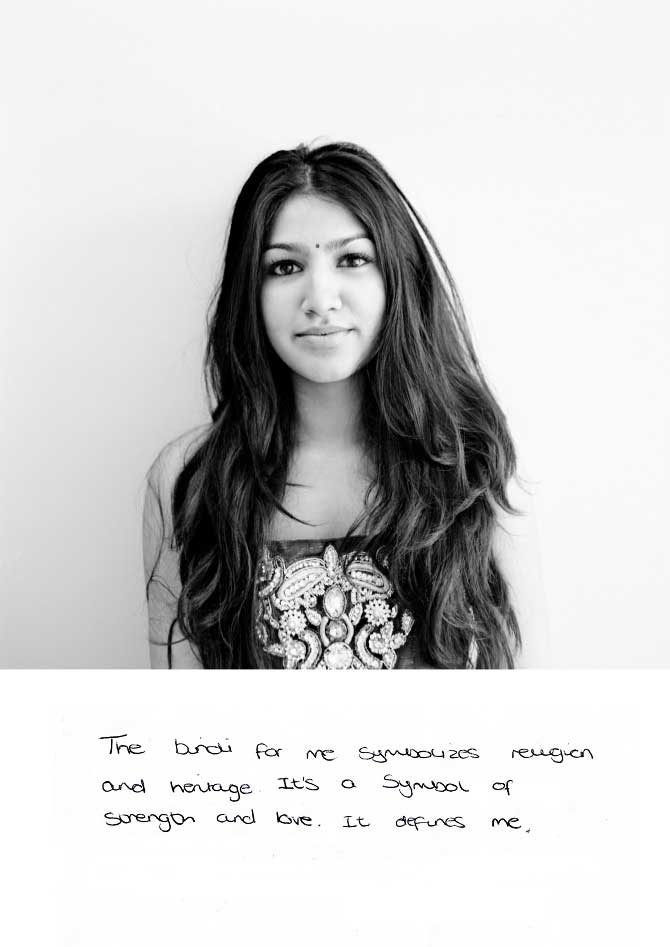

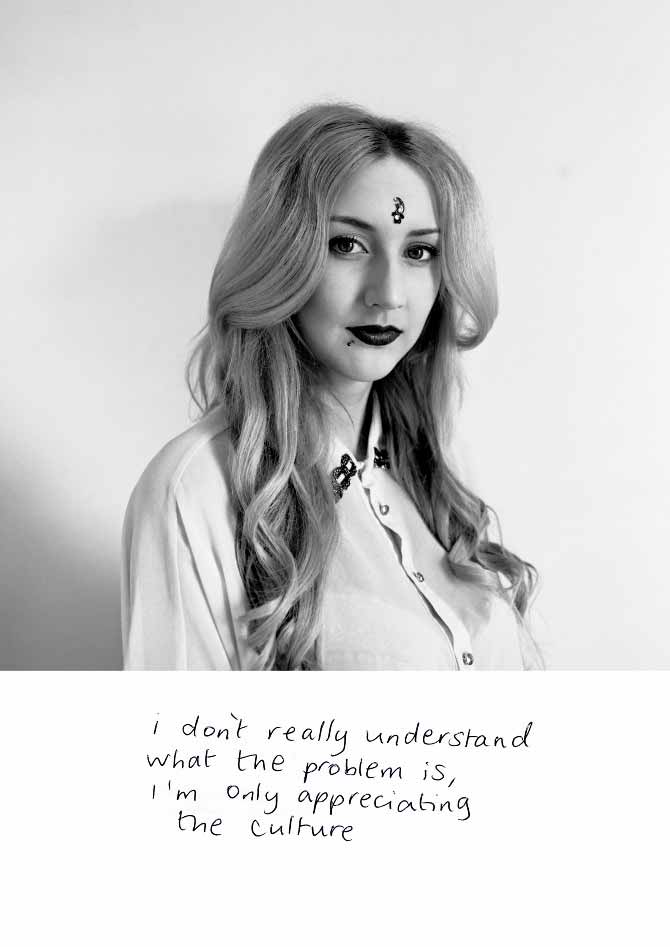

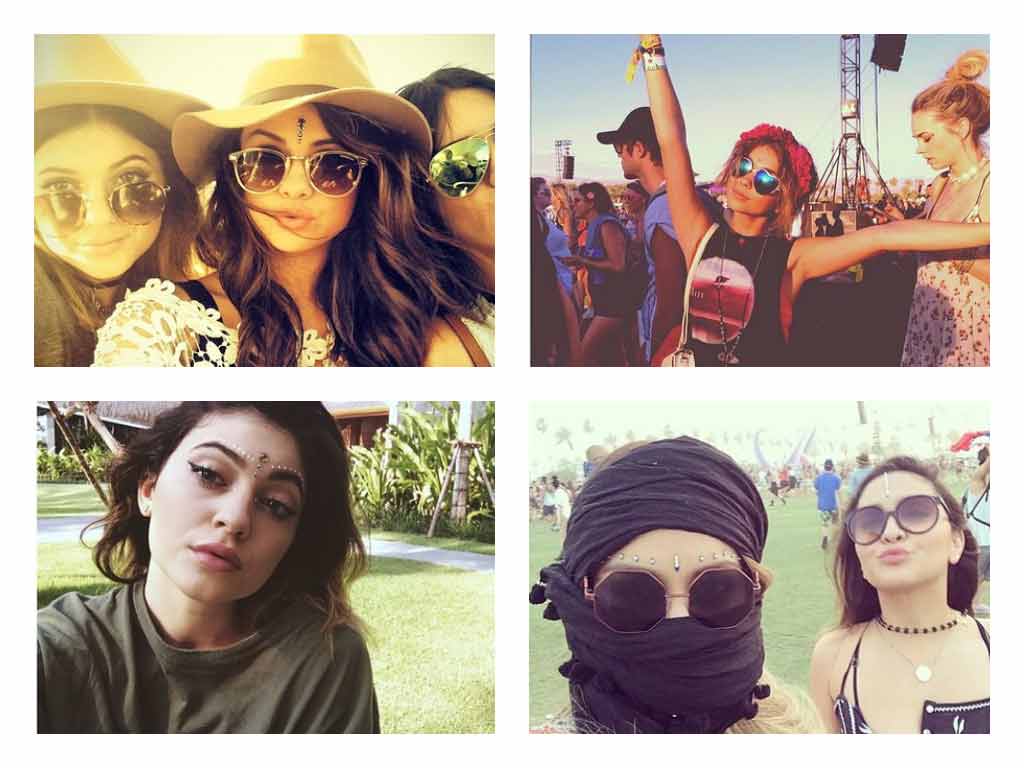

The phenomenon of people appropriating culture – for example, the bindi equating exoticism, grunge and hipster fashion – goes least checked in India. Selena Gomez wore a bindi and received startlingly little critique. The Jenner-Kardashians sported them at Coachella. What used to be a symbol of wisdom, spirituality, and belonging is now whatever the white narrative dictates. Clad in cultural tidbits stripped of their contextual dignity, Iggy Azalea went so far as to shoot a music video on a grossly irrelevant Indian wedding and temple backdrop. It’s glamorous when they do it, but on our own complexions, they’re now uncomfortable and ‘backwards’.

We Indians are hardly irritated by this double standard, of course. In fact, we’re kind of flattered. It’s a white person engendering glamour and appeal into a culture whom we ourselves attribute with neither quality! White people are precisely our sole source of aesthetic validation.

This is a ubiquitous and almost uniquely Indian phenomenon in its extent.

Centuries of colonialism have reshaped every ideal of Indian Culture: to be educated is to speak English, to be progressive is to wear Western clothes, to be beautiful is to be fair-skinned. In order to ‘assimilate’ and please our white friends, we deliberately pronounce words we know how to pronounce right wrong and reassure them, that we, in fact, cannot speak a word of Hindi. The successful Indian is one who has sufficiently dissociated from his/her own culture to an unrecognisable degree. The successful Indian exchanges the detritus of the Indian passport for the sanctified red travel papers as soon as he can, changes his name to a curtailed, white-sounding moniker and is never seen wearing a kurta during daytime. The successful Indian is fluent in American English and pronounces namaste, tandoori and karma incorrectly. The successful Indian is deliberately un-Indian. The successful Indian supports both cultural derision and the historical erasure of the bloodsheds of the British Raj. The successful Indian effectively, deeply, hates himself and his culture only appeals to him when it is endorsed by a white person.

The successful Indian is one who has sufficiently dissociated from his/her own culture to an unrecognisable degree. The successful Indian exchanges the detritus of the Indian passport for the sanctified red travel papers as soon as he can, changes his name to a curtailed, white-sounding moniker and is never seen wearing a kurta during daytime. The successful Indian is fluent in American English and pronounces namaste, tandoori and karma incorrectly. The successful Indian is deliberately un-Indian. The successful Indian supports both cultural derision and the historical erasure of the bloodsheds of the British Raj. The successful Indian effectively, deeply, hates himself and his culture only appeals to him when it is endorsed by a white person.

When you disown your culture and take pride in another, you are telling the oppressor that he has achieved the ultimate victory, because you yourself display that the culture was not worthwhile. If you cannot stand up for the centuries long exploitation of a victim country and demand respect for its historical relics, you are on the side of the oppressor.

Truth is, a colonialism of identity still burgeoning in India: this phenomenon of growing self-hate and indifference to appropriation amongst Indians is a pitiful crisis that we ourselves can change immediately. Change begins with self acceptance.

Featured image from: http://thesheaf.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/cultural-appropriation-rectangle-1100×722.jpg

Still images courtesy of: http://www.sanaahamid.com/Cultural-Appropriation-A-Conversation